Our industry has a problem. This became abundantly clear to me when I attended the VHMA Critical Issues Summit on Pricing in Chicago earlier this month. The summit began with a presentation from Dr. Karen Felsted of PantheraT Consulting who set the stage for the conversation to follow. Presenting data from both the Veterinary Hospital Managers Association (VHMA) and the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), Dr. Felstad raised a number of concerns related to the recent history of veterinary pricing practices in the profession.

Veterinary prices have been increasing faster than inflation for nearly two decades

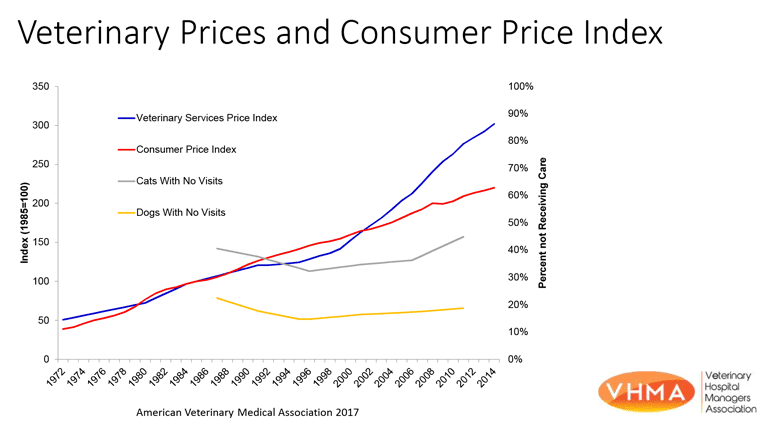

Consider the chart below. With little precision, practices have been applying price increases of, on average, four to five percent per year to all of their products and services across the board. (Prices are actually increasing faster than the median household income.)

The net effect, as you can see here, is an increase in the percentage of pets who are not receiving care.

This is bad news.

Not only for veterinarians, their staff and their practices, but also for their patients and the people who love them.

It’s time for the veterinary industry to revisit its pricing practices

Recognizing the gravity of the situation, the VHMA invited Dr. Utpal Dholakia — a pricing expert from the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University and author of How to Price Effectively: A Guide for Managers and Entrepreneurs — to facilitate discussions around best veterinary pricing practices within the industry.

Recognizing the gravity of the situation, the VHMA invited Dr. Utpal Dholakia — a pricing expert from the Jones Graduate School of Business at Rice University and author of How to Price Effectively: A Guide for Managers and Entrepreneurs — to facilitate discussions around best veterinary pricing practices within the industry.

Together, Dr. Dholakia, Dr. Felsted, and other attending industry leaders put their heads together and developed a series of recommendations to improve pricing practices while maximizing patient care.

You can download that free whitepaper here.

Current veterinary pricing practices fail to consider practice overhead

According to long-time industry veterans, practices usually price their products and services by applying a simple markup to the cost of the good. This approach is intuitive and straightforward, although for reasons to follow, it may not be best practice.

According to long-time industry veterans, practices usually price their products and services by applying a simple markup to the cost of the good. This approach is intuitive and straightforward, although for reasons to follow, it may not be best practice.

Services are marked up from the cost of the labor (doctor, vet tech, etc.) required to deliver them. Inventory is treated much the same way, with standard markups of 100% percent, plus a pharmacy fee, or 50% plus fee for more expensive products. Some clinics go the extra step of surveying prices offered by other local hospitals for comparison.

The trouble with this approach is that practices often fail to adequately account for expenses that are not direct costs of providing products or services, but that are nonetheless essential. These are the fixed costs of running the practice, i.e. overheads like rent, utilities, maintenance, advertising, marketing, and bookkeeping. Many practices don’t account for these in their pricing, which means they’re either getting lucky when their markups happen to cover them — or they aren’t.

[bctt tweet=”Many veterinary practices fail to adequately account for the fixed costs of running their practice when establishing their pricing structures.”]

A better practice — one that accounts for overheads — is to distribute the total of fixed costs into the costs of core products and services, and then apply a markup on top of that. At minimum, it means a hospital will cover their total costs (overheads plus the variable costs of their core products and services), what Dholakia refers to as their long-term price floor.

But this is only half the picture. The other half is much more exciting.

Practices should be putting price structure before price level

Consider the classic gambit that grocery stores use on Thanksgiving. Give a turkey away for free, knowing full well that shoppers will buy the rest of their groceries at that store. It’s the other groceries that turn a profit, which, if priced properly, more than cover the free turkey.

Consider the classic gambit that grocery stores use on Thanksgiving. Give a turkey away for free, knowing full well that shoppers will buy the rest of their groceries at that store. It’s the other groceries that turn a profit, which, if priced properly, more than cover the free turkey.

What this implies is that businesses have a price level, the average price of all their products and services, and a price structure, which is the variety of products, offers, and benefits that a business offers its customers. As long as the price level successfully covers costs and margins, prices can be structured — both above and below cost — in such a way as to increase both customer value and practice returns.

The Thanksgiving turkey is a standard example of a “loss leader,” a product or service offered below cost in order to attract customers. Other products and services are priced to compensate, leaving the price level unaffected, while varying the pricing structure.

These and other approaches, which will be covered in the forthcoming white paper, can be helpful elements of a sophisticated pricing structure that can bring more clients in the door and enable more patients to get the care they need, while keeping the lights on and the bills paid.

New products and services present an especially good opportunity for an effective pricing structure

[bctt tweet=”If a practice has successfully covered their total costs with core products and services, this frees them to introduce new products and services at a much lower price than expected.”]

Consider Happy Hour at a fancy restaurant. The core products and services — namely, the dinner service from 6pm onward — have to be priced to cover the restaurant’s fixed costs (rent, equipment, salaried employees, etc.), plus the variable costs of the dinner service (essentially the food and wait staff).

Once these costs are covered, the restaurant is then free to add a whole other product line — Happy Hour — at a fraction of the price. When pricing Happy Hour, the restaurant need only consider (largely) the associated food costs and wait staff. All the overhead costs are covered by dinner. As a restaurateur said to me recently, “cover your costs at dinner and everything else is gravy.” (Pun intended.)

Want to introduce a pick-up and drop-off service? Price it relative to the additional costs — perhaps additional boarding space and some staff time — and don’t worry about the rest. It’s already being covered.

Veterinary pricing practices should be guided by your value proposition

While the above tactics and approaches may help you develop a more sophisticated pricing structure, the heart of the matter is your practice’s value proposition. It is and should be the driving force that guides all pricing decisions, establishing the point of departure from which a practice prices and to which it returns.

It is the answer to the question: “Why should a client choose your veterinary practice over another?” Is it because you offer the lowest prices, the best quality, the best value for dollar, or some other set of advantages?

Look at ventures in other industries and you can see how the value proposition becomes central to pricing structure. Take a luxury car manufacturer. They don’t scruple about setting high prices, because their product is high quality. (And, incidentally, we also interpret high prices as a marker of high quality. But making good on that marker is essential.) A low-cost department store takes pride in offering the lowest possible prices, even agreeing to match or beat competitor prices, because it is their value proposition.

Signals of a business’s value proposition can even be reflected in the finest pricing detail. Highest quality goods and services, like luxury clothing brands or high-end restaurants, typically round their pricing to the nearest dollar. Low-price establishments, by comparison, typically end their prices in 97 or 99 cents.

What is your practice’s value proposition? How is it reflected in your pricing structure? How should it be reflected, so that it sends a clear and present message to your customers about who you are and what you stand for?

The best way to approach your pricing structure? Test prices by changing them

Dr. Dholakia’s recommendation is to adjust the prices of your three most popular services for a month and see what happens. (He suggests increasing them by $5 or 5%, whichever is smaller.) You can always change them back, but at least you’ll learn something about your customers and their demand for your services — for example, whether they are highly sensitive to price changes or not.

[bctt tweet=”The best way to approach your pricing structure is to test prices by changing them. Pricing expert Dr. Utpal Dholakia suggests experimenting with your 3 most popular services for a month.”]

More valuable insights on veterinary pricing practices await

Hats off to James Nash, Brian Conrad, and Christine Shupe of VHMA for convening the summit on this pressing topic. I, for one, am very much looking forward to reading the white paper. No doubt you are, too. It promises to be an interesting and impactful read.

Kevin Keystone is the former Head of Product for VetSuccess. .